No More Juiced Balls: How to Approach Hitters in 2022 Fantasy Baseball Drafts

Baseball has changed throughout the years. If Ty Cobb, master of the “inside game” featuring singles and stolen bases, fell asleep in 1909 and woke up in 2021 his brain would explode. It’s easy to spot the game style differences from our national pastime when zooming out and looking at 100+ years. It’s typically more difficult to recognize developments as they’re happening, but that isn’t the case entering 2022.

A major reason for this has been the interjection of Major League Baseball themselves. Whereas changes such as defensive shifting and utilizing “openers” have altered our sport, those were tactical decisions by managers that evolved naturally. Enforcing the ban of “sticky stuff” came from league offices. The implementation (and then removal) of juiced balls was partly MLB’s own doing. Regardless, it was an external change to the game of baseball that has had an incredible impact.

A lot has been written and said about these choices. This two-part series is less concerned with whether or not they were the right decisions. Instead, let’s focus on what it all means moving forward. We’ll be starting with the juiced ball.

By better understanding the recent past, baseball fans will be in a stronger position to succeed in fantasy leagues, profit from DFS, and win bets, in addition to becoming better critical thinkers to project the future.

The Juiced Ball: A Brief History

If there’s one way to summarize MLB since 2015, the term “Juiced Ball Era” is it, and we’ll start with analyzing what that phrase even means.

Once steroid testing was officially implemented in 2004, baseball spent a decade shifting towards a product that featured more athletic, well-rounded athletes. Gone were bulging biceps and 60+ homer campaigns. An emphasis on analytics, bullpen usage, and multi-dimensional stars began taking over.

Six of the 23 perfect games in MLB history were clustered between 2009 and 2012. Sports Illustrated dubbed 2010 as “the year of the pitcher.” Think of the 2014 Royals and the early-teens Giants as confirmation of baseball exiting the Steroid Era.

2015 seemed like more of the same. A new era, with its own unique style, had arrived. Then, suddenly, there was a spike in the league-wide home run to fly ball rate in the second half. Before the 2015 All-Star game 10.7% of fly balls turned into homers that year. Afterwards? 12.1%, which would’ve represented a single-season high in Fangraphs’ batted-ball tracking era (since 2002).

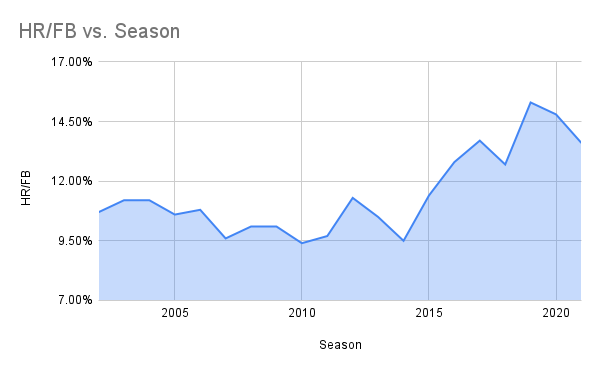

As evidenced below, the next few years saw multiple single-season highs in MLB-wide HR/FB%.

During the early days of the Juiced Ball Era there were a lot of questions, and theories, as to what was going on. In 2017 Ben Lindbergh of The Ringer wrote a fantastic piece outlining the possible reasons for baseball’s “air ball revolution.” The full article is worth reading, but to summarize, the ball itself has always been the likeliest culprit. That is especially true with the benefit of hindsight.

Let’s quickly catch our breath and take a second to remember that we aren’t here for juiced ball conspiracy theories or to debate the science of it all. We’re focusing on what happened on the field in order to better project what might happen moving forward.

What we know is that since the second half of 2015 fly balls have been turned into homers at a higher rate than every season that came before it (again dating back to 2002).

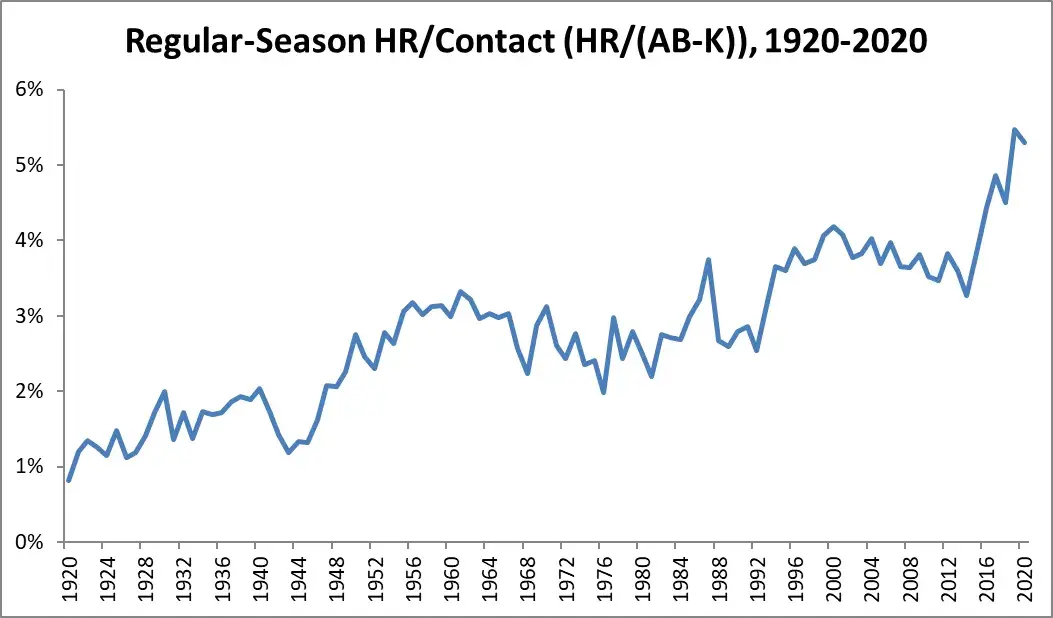

In fact, home runs on all batted ball events have spiked as of late. The below image is from another Lindbergh article, which can be found here.

2019: The Summer That Got Out Of Control

What I want to focus on next is the uniqueness of each year within the Juiced Ball Era, and specifically what occurred during 2019. One of the defining features of the Juiced Ball Era has been the year-to-year changes and volatility.

As of this writing 2019 has been the unquestioned height of the Juiced Ball Era. Given MLB’s recent intervention with a “deadened” ball, I’m anticipating this remaining the case.

Remember 2019? My goodness that was a wild ride. The league set a new record for homers that season with a whopping 6,776 long balls, a drastic spike from the second-highest total of 6,105 from 2017. (Four of the top five homer happy seasons are from the Juiced Ball Era).

The four highest home run totals per season by individual teams, in MLB history, all came in 2019 (plus 10 of the top 21)! The Twins led the pack, who also set records for the highest number of 20-homer hitters on a team (eight) and 30-homer bats (five).

From May 26th through July 1st the Yankees went 31 consecutive games with a dinger, which, of course, is also a MLB record.

This was Pete Alonso’s 53-homer rookie year. Eugenio Suarez randomly hit 49 homers; Jorge Soler hit 48. These weren’t records, but the Juiced Ball Era has never been about one or two sluggers recreating the Summer of ‘98. It has been about the types of hitters who could be elevated in the power department (more on this in a bit).

Alex Bregman took advantage of these extra-juicy balls, belting 41 homers in ‘19. Xander Bogaerts posted career-best power numbers. Anthony Rendon had an outlier campaign. DJ LeMahieu went on a two-year heater despite leaving Colorado and Coors Field.

These are all good players. They weren’t simply products of 2019, but they represent hitters who took advantage of a new environment, only for their offensive stats to regress with the introduction of the “deadened” ball in 2021. Other examples include Yoan Moncada, Francisco Lindor, Trey Mancini, Michael Brantley, Cavan Biggio, and Jeff McNeil.

As CBS Sports’ Scott White showed earlier this offseason, there exists a relationship between exit velocity and home run output. Throughout the Juiced Ball Era batters simply didn’t need to impact the ball as hard to hit a homer as they otherwise would’ve. And that was never more true than in 2019.

Lessons Learned

I am very curious to see where the league-wide HR/FB% goes moving forward. 2021 was the first year with the deadened ball, kind of, but it still behaved as the continuation of the Juiced Ball Era. Here are the yearly HR/FB rates (non-graphical form) since the ball was first introduced:

2015: 11.4%

2016: 12.8%

2017: 13.7%

2018: 12.7%

2019: 15.3% (!!)

2020: 14.8%

2021: 13.6%

So it isn’t as if ‘21 was a return to anything that came before the air ball revolution. Now, will an actual full season’s worth of deadened balls lower the rate? Probably. Other factors have been in play lately — an increased emphasis on launch angle, human evolution, strategies around the long ball, etc. In general, the home run is likely here to stay for a while.

The de-juiced ball is a big deal, but when compared to baseball’s history as a whole, present day hitters are still encouraged to lift the ball.

However, my No. 1 takeaway from this research is that we need to re-think 2019’s place in history. MLB is implementing the deadened ball and banning sticky stuff with hopes to create a neutral environment. The more data we get moving forward, the better we will get at projecting future seasons.

Consider the process of projections for the past five years. We never knew what ball we would get heading into a season, then we got an extra-juicy one, then we had a pandemic-shortened campaign, and then the deadened ball this past summer. Oh, and sticky stuff was suddenly banned at midseason. It has been a nightmare.

Better days are ahead for projection analysts, but let’s always make sure to evaluate 2019 in the right context. Even for the Juiced Ball Era, it’s shaping up to be an outlier.

Final Thoughts

My other takeaway is to consider the type of hitters who benefitted the most from extra-bouncy baseballs.

The Juiced Ball Era has featured a home run frenzy that blows the Steroid Era out of the water, and the reason is that nowadays nearly every hitter is benefitting.

During the Steroid Era, PEDs helped hitters stay on the field when they might otherwise be battling a minor ailment. Players who used PEDs were able to chase higher homer totals than we previously thought was possible. Meanwhile, not everyone used PEDs, but everyone has been subjected to these new baseballs.

By the end of the 2019 campaign there was a strong argument to be made that investing early in high-end starting pitchers was the optimal move for fantasy managers. There were so few of them, and there were so many hitters to go around.

“Breakout bats” such as Bregman could be scooped up in the middle rounds. 20-homer hitters could reliably be found late in drafts.

Then, everything changed when the fire nation attacked.

In other words, MLB intervened.

2019 was different from the rest of the Juiced Ball Era, but that ball is no longer around. Don’t put as much stock into individual player stats from that year. Simultaneously, be more willing to target proven, elite hitters earlier in drafts this spring.

In part 2 of this series we’ll be looking at how MLB’s sticky stuff enforcement, combined with the new ball, could lead to a new approach for drafting starting pitchers in 2022.