The Dirty Dozen: Jim Brown and the Most Dominant Running Backs in NFL History

On Friday, the NFL world came to a halt to acknowledge the death of Jim Brown. Brown’s on-field legacy hardly needs introduction – one of the greatest players of all-time, and on occasion named the very best to have ever done it, Brown’s impact on his position, on the NFL, and on professional football as a whole is right up there with anyone else who has ever played the game.

In the days since, tributes, memorials and, yes, criticism has poured in as the football world has tried to come to grips with Brown’s passing. One common theme is to attempt to put Brown into context for modern football fans. After all, Brown’s last snap came in 1965, long before most NFL fans were alive. Brown exists in highlight films and documentaries, in interviews from his contemporaries and praise from his successors. Very few of us got to see Brown as an actual football player; he’s been a legend since we first learned what the game even was.

And so, people have been trying to figure out where Brown stands and ranks among his peers. His place in Browns history. His place among the best NFL players ever. The best individual seasons for a running back; the best rookie seasons regardless of position. Brown’s high on them all, as he should be.

As I was thinking about Brown, and reading all of the praise that has come his way over the past few days, the phrase that kept coming up over and over again was dominance. Brown wasn’t just great, he was dominant, able to shape gameplans and seasons by the sheer force of his skill. Someone who, at his very peak, was as close to unstoppable as anyone in the league has ever been.

Ranking running back dominance is an interesting exercise. It’s distinct from greatness, where issues like longevity and championship rings start coming into play. You can argue that, say, Frank Gore had a greater career than Terrell Davis thanks to a decade and a half of good to great play. But you can’t argue that he was more dominant at his peak than Davis was, when he was in full health and at full force. Brown’s position as greatest running back of all time can at least be challenged because of his decision to retire early to focus on his film career, but can anyone hold a candle to Brown when he was at his very best?

With that question in mind, and with a tip of the hat to Brown’s film career, I’ve set out to find my own Dirty Dozen – the 12 most dominant running backs in NFL history. This is in large part a subjective ranking, though there was significant time and effort spent looking at MVP and Offensive Player of the Year voting; advanced stats for players who have them and traditional stats for players from older eras. Ultimately, the criteria was simple: if I could have just three or four of a running backs’ best years, who would come out on top?

We’re looking at the NFL first and foremost, and modern-day conceptions of what a running back is. So, with all due to respect to Marion Motley, Steve Van Buren and Dutch Clark, here are my picks for the 12 most dominant running backs in the history of the league.

12. Emmitt Smith

Dallas Cowboys (1990-2002), Arizona Cardinals (2003-2004)

I grew up rooting for the San Francisco 49ers in the late 1980s and early 1990s, meaning I saw plenty of the Triplet-era Cowboys when I was developing as a football fan. And let me tell you, for elementary school-age Bryan, it wasn’t Michael Irvin who terrified me (though I’ve since come around on his greatness). Nor was it Troy Aikman, who I still believe is ‘just’ a very good passer with great players around him. No, the Cowboy who terrified me every season when San Francisco and Dallas would inevitably meet in the playoffs was Emmitt Smith.

Smith may not have been the fastest runner in the world, but his feet never, and I mean ever, stopped churning. His leg strength and balance were unparalleled in the 1990s, letting him ping off and through tacklers as if they simply were not there. He could dig an extra yard or two out of nowhere, rarely going down on the first hit. When coupled with that Dallas offensive line in the early ‘90s, had plenty of room to build up a head of steam that allowed him to just become an unstoppable force headed towards the end zone. Smith is the only player in NFL history to win a Super Bowl, Super Bowl MVP, regular season MVP and rushing title in the same season – and, with the way the league is currently going, likely will remain the only player to do that. He led the league in rushing four times in five years between 1991 and 1995. The one year he missed out? He led the league in rushing touchdowns, despite nursing a sore hamstring throughout December. Despite two other Hall of Famers at skill position players, opposing teams based their strategies against Dallas on shutting down Smith. More often than not, they failed.

Despite being the all-time leading rusher in the NFL, Smith is just 12th on my rankings because of the overwhelming power of his offensive line, as well as the fact that his career totals are padded by his longevity. Longevity is very important when we’re determining the best running backs of all time, and the fact that Smith was able to play at a high level for a decade is a huge argument in his favor there. Smith is likely in my top five if we’re judging total career value. But in terms of sheer peak dominance, Smith drops a few slots.

11. Larry Brown

Washington Redskins (1969-1976)

Brown’s rushing style likely led to his relatively short career as a star running back. Never one to shy away from contact, Brown was willing and able to run over defenders even at 195 pounds, small even by 1970s standards. Put Brown next to Larry Csonka or John Riggins, and you’d assume he would be a nice change of pace back, or a pass-catching alternative for desperate situations. But no; Brown has an argument as being the toughest runner of the three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust 1970s. One the premier downhill runners of the era, if you were in his way, you either were going to get thrown aside or trampled over.

The 1972 MVP, Brown lead the league in yards from scrimmage between 1969 and 1972 – not Csonka, not O.J. Simpson, not Leroy Kelly or Floyd Little, but Brown. Brown had 18 100-yard rushing games between 1970 and 1973; only seven players had more than that given the whole decade to work with. He was just the third or fourth player in NFL history to average 100 rushing yards per game, depending on how you count Jim Nance in the AFL. Brown led the league in rushing in 1970, despite missing a game due to injury. He led the league in yards from scrimmage in 1972 despite missing two games. And all this is before you mention his receiving ability, which was exceptional for the era – his 2,183 receiving yards in the 1970s are eighth-most among running backs, as he was equally fearless going across the middle on pass-catching routes as he was running through defenders. Nor does it mention his blocking prowess; you could make an entire highlight reel of guys he blew up in the backfield.

Brown’s hard-nosed style made him, and it broke him. Numerous injuries, most notably to his knees, sapped him of his explosiveness as George Allen almost literally ran him into the ground. The short peak is why he’s not in the Hall of Fame. The fearless rushing is why he makes my top dozen.

10. Adrian Peterson

Minnesota Vikings (2007-2016), Arizona Cardinals (2017), New Orleans Saints (2017), Washington Redskins (2018-2019), Detroit Lions (2020), Tennessee Titans (2021), Seattle Seahawks (2021)

Unless the NFL fundamentally changes its rules to promote rushing over passing, Peterson is likely the last running back MVP the league will ever see. He’s likely the last sure-fire lock Hall of Fame rusher the NFL will ever see, as well. There may not be a more impressive feat for any running back ever than rushing for 2,097 yards in a season less than a year removed from a torn ACL and MCL – not to mention doing it while suffering through a hernia for the last month of the year.

You simply were not supposed to be successful as a running back in the 2010s running the lead draw – letting a fullback pave the way and taking advantage of that blocker to churn up extra yards. The league was already shifting the zone-blocking oriented league we take for granted today. But Peterson had the combination of speed, power and explosiveness to make that old-school style work. In that early-2010s prime, Peterson took on more of a workload than any modern back – he’s the only rusher whose career started in 2005 or later with four seasons of 300+ carries – and he did it without ever really slowing down or succumbing to the pressures of being a throwback lead back in an era of committees. Peterson’s career 4.6 yards per carry are fifth-most among the 31 backs in the 10,000 yard club, and he was running at an even 5.0 yards per carry in his 2008-2012 prime, all while carrying the Minnesota offense on his shoulders.

9. Terrell Davis

Denver Broncos (1995-2001)

The platonic ideal of the all-peak, no-longevity legend, Davis was done as a contributor after the 1998 season, with knee injuries essentially ending his career after four years. Those four seasons included three first-team All-Pros, two offensive player of the year awards, an MVP, a rushing title, two rushing touchdown titles, two Super Bowl rings, a Super Bowl MVP, and a spot on the 1990s All-Decade team. Not bad work, if you can get it.

Davis’ regular season numbers are impressive enough – the 2,000 yard season in 1998, the 97.5 yards per game that remains the third-best mark in NFL history, his exceptional vision and the nastiness that led to him running over guys in his way. But you could also look at the success other running backs had in Mike Shanahan’s system and wonder if Davis was simply a very good back in an elite system.

Then you watch the playoff games again, and you have your answer. Davis played in eight postseason games. In every single one, he ran for at least 90 yards, and topped 100 in all seven games of his two Super Bowl runs – shining brightest when the spotlight was on him. Davis is tied with Emmitt Smith for the most 100-yard rushing games in the postseason, and he did it in such a compressed amount of time. It’s impressive to say that the postseason really made the legacy for the only player with 2,000 rushing yards and 20 rushing touchdowns in the same season, but really, it did. If you include playoff games, the most rushing yards in one season belongs to Davis, with 2,476 in 1998. In second place? Davis again, with 2,331 in 1997.

8. Eric Dickerson

Los Angeles Rams (1983-1987), Indianapolis Colts (1987-1991), Los Angeles Raiders (1992), Atlanta Falcons (1993)

We’ve had plenty of bruisers on this list. Dickerson is not one of them. Mind you, he could run over guys when he needed to, but Dickerson’s calling card was a grace and fluidity so natural it looked like he was hardly trying – until he turned on the jets and raced right by you. Some of the previous entries on this list were monster trucks. Dickerson was a racecar. A former high school track star who ran a 9.4-second 100-yard dash, Dickerson was essentially impossible to catch from behind. By the time you noticed him running at you, he was already five yards past you. There’s an argument to be made that he was the single-most explosive rusher of all time. There’s very little argument he wasn’t the smoothest.

Dickerson’s 2,105 rushing yards in 1984 remain the all-time NFL record, only really challenged five or six times since. It wasn’t on the back of a ton of huge plays, either – while Dickerson ran for 5.6 yards per carry, he only had two 50+ yard runs. It was just six or seven yards play in and play out; efficient to no end. Dickerson was far from a one-hit wonder, too – as the Los Angeles Times put it, the leaves turn, the sun rises, the world spins and Eric Dickerson gains 1800 yards in a season. Dickerson is the only player in league history with three 1800-yard rushing seasons. They were in three of his first four seasons in the league, and the one year he fell short? That was the year he sat out two games while in a contract dispute with the Rams. And he went on to rush for 248 yards in a playoff game anyway, still the NFL record. He became the fastest player to reach 10,000 yards, though injuries, age and more contract disputes slowed him down after being traded to the Colts. For those first four years, however, no one could catch Dickerson.

7. Barry Sanders

Detroit Lions (1989-1998)

If this was a list of the best highlight reels in NFL history, Sanders would be number one by a landslide. Stopping, starting, cutting back, spinning, going from 0 to 60 in the blink of an eye, Sanders did things you’re only supposed to be able to do in video games. Sanders is, without a doubt, the greatest boom-and-bust rusher in history. Sometimes, his dancing in the backfield would cause what would be a two-yard run for most backs into a stop behind the line. More often, however, he’d take hopeless situations and make magic happen. As one of only two running backs in NFL history to average five yards per carry over at least 2,000 carries, Sanders boomed like few others have ever boomed.

One of the hardest parts of doing any all-time list like this is digging up long-buried arguments of the past and taking sides. The great running back debate of the 1990s was Sanders against Emmitt Smith – the dancer against the powerhouse. For me, I’d take Sanders 10 times out of 10. I’ve always valued elusiveness in my running backs, and Sanders may as well have been a ghost. Smith was running behind one of the best lines of all time. The Detroit line did not have to block as well as Dallas’ did, because tackling Sanders one-on-one was a fool’s errand. It didn’t matter if the blocking scheme was outnumbers up front – the free defender was Barry’s guy to make miss. And it worked far, far more often than it had any right to.

Unlike many of the other names on this list, Sanders was still at his peak when he retired, or at the very least very need it. Fed up with poor management in Detroit, Sanders retired just one year removed from his 2,000 yard season, still averaging over 90 yards per game on the ground. Had he tacked on some end-of-year careers, I have no doubt he’d be the all-time rushing leader to this day.

6. Earl Campbell

Houston Oilers (1978-1984), New Orleans Saints (1984-1985)

Campbell started his career leading the league in rushing three years in a row, earning an MVP, a Rookie of the Year, and two Offensive Player of the Year awards for his troubles. He also started his career with thighs the size of tree trunks and energy to match, with his sledgehammer rushing style shredding opponents. It is possible poor Isiah Robertson – a six-time Pro Bowl linebacker – is still embedded in the turf from trying to stop the rookie from Texas. Luv Ya Blue? More like Luv Ya Black and Blue if you got in Campbell’s way.

Before the wear and tear finally wore him down, tackling Campbell was the least-desired job in professional football. The accolades from legendary defenders of the day are endless – Joe Green said that no one in the history of the league possessed the power and speed Campbell had, and Cliff Harris once said the only way to tackle Campbell was to close your eyes and hope he didn’t break your helmet. Bum Phillips was once asked if Campbell was in a class all by himself. “If he ain’t,” the legendary coach replied, “it don’t take long to call the roll.”

When it comes to just pure, unadulterated power, there may have been no one better than Campbell. His style, and the heavy workload that came with it – 1,404 attempts in his first four seasons, second-most in NFL history behind Eric Dickerson – wore him out before his time. But if the MVP, rookie of the year, three straight rushing titles and three straight Offensive Player of the Year awards aren’t enough to convince you just how hard it was stopping Campbell, then the litany of bruised and battered defenders in his wake should.

5. LaDainian Tomlinson

San Diego Chargers (2001-2009), New York Jets (2010-2011)

The jukes and escapes of Barry Sanders may never be topped. But if you’re looking for precision and fluidity in your cuts, the ability to change direction without dropping a step or slowing down, I’m not convinced there’s ever been anyone better than Tomlinson.

At the very least, a back as elusive as Tomlinson had no business being as tough inside the tackles as Tomlinson, whose stiff arm left defenders floundering in their wake. And no one as tough inside the tackles should be as good as catching the ball as Tomlinson, who led all running backs with 4,323 receiving yards in the 2010s. Tomlinson was a complete back in every sense of the word, to the point where he ranks second in the modern era with seven passing touchdowns from the position. An absolutely ridiculous skill set – and so much of it happening during the fantasy boom, too. Tomlinson has the first, fifth and 18th most PPR points in a single season for a running back ever, something that has become part of his legend. He may be pipped to the line by Emmitt Smith in total fantasy points, but many, many more people were playing when Tomlinson was active, and he won many a fantasy manager a championship or three.

Tomlinson’s MVP season in 2006 deserves more acknowledgement. It sometimes gets lost in the shuffle of great running back seasons because he “only” had 1,815 yards from scrimmage. But he set records in touchdowns (31), rushing touchdowns (28) and points (186). Only one season since has produced more DYAR than Tomlinson’s combined 581 rushing and receiving that season. We don’t see years like that much anymore – players who dominate in the open field, as a pass-catching back, and as a goal-line threat. Tomlinson was all of that and so much more.

4. Walter Payton

Chicago Bears (1975-1987)

For my money, Payton, not Jim Brown, is the best running back of all time. Payton slips a couple slots on pure short-term dominance, never having that 2,000 yard rushing season and only leading the league in rushing yards once. He’ll have to settle for ‘only’ finishing in the top five here. Darn.

So much of Sweetness’ legacy comes from his toughness and longevity – playing through fractured ribs, separated shoulders, banged up knees and sprained ankles. Starting 170 consecutive games with a playstyle that saw him running into and through defenders, daring them to get up before he did? It’s unfathomable in today’s era, and a large part of why he held the rushing record for years. On top of that, Payton retired with more receptions than any running back in NFL history to that point. No one in NFL history has more 100-yard games than Payton; his stutter-step, glide and stiff-arm causing defenders to rethink their professions.

But the sheer weight of the career numbers sometimes distracts us from the fact that Payton was a stud in his peak, too. In his MVP year in 1977, Payton averaged 132.3 rushing yards per game, third-most in NFL history. And he did it on an offense with no support – Bob Avellini at quarterback? James Scott and Bo Rather at receiver? An offensive line composed of whosits and never-weres, none of them even in their third NFL season at the time? Payton was the sole functioning part of that Chicago offense, and managed to lead the league in carries and yards per attempt, in the absolute heart of the dead ball era, with every defender on the field knowing that he was touching the ball on nearly every play. Never has so much been done by a player surrounded by so little.

3. Marshall Faulk

Indianapolis Colts (1994-1998), St. Louis Rams (1999-2005)

This is the one I realize I’m going to have to defend the hardest; the most surprising entry in the top five. And if we were composing a list of pure running backs, emphasis on the running, than Faulk probably would not have cracked the top dozen – after all, he never cracked 1,400 yards in a season. But playing running back is more than about taking handoffs. As a complete player, Faulk’s legacy with the Greatest Show on Turf is, in my mind, unparalleled. As a receiver and rusher, there has never been a better football player than Faulk.

I’m a sucker for nice round numbers and arbitrary targets. The 1,000-1,000 club is one of my favorites, as only three players in history have managed a thousand rushing and receiving yards in the same season – Faulk, Roger Craig and Christian McCaffrey. Faulk’s thousand-thousand came in 1999, when the Rams exploded into the stratosphere, shattering records for points scored and offensive yards. Advanced stats aren’t quite as kind to those Rams, noting their relatively weak schedule. But oh, do they love Faulk.

Football Outsiders currently has DYAR stretching back to 1981. Faulk had 757 combined rushing and receiving DYAR in 1999, third-most ever for a running back. In 2000, Faulk had 846 DYAR, most ever for a running back. And in 2001, Faulk had 707 DYAR, fifth-most ever for a running back. Three of the best five seasons we’ve seen in 42 years, in a three-year stretch. And, in case you think that’s just a matter of playing on the spectacular Rams teams, Faulk’s 1998 season in Indianapolis? That sits at 647 DYAR, eighth-best in NFL history. Yeah, that’s pretty good.

Faulk won MVP in 2000, and was second in the voting in both 1999 and 2001, finishing behind his quarterback Kurt Warner each time. But more than just the raw numbers and the accolades, Faulk’s playing style appeals to me aesthetically more than anyone else on top of this list. I like my running backs to be able to run route trees, to be able to win matchups when split out wide, to be a threat on all downs and distances. Faulk is the predecessor to the McCaffreys and Alvin Kamaras of today, the archetype that continues to show its value even as the traditional power running back sees their career getting shorter and shorter and their contracts getting lower and lower. Faulk is the platonic ideal of the running back I want on the offenses I want to see. And just because he didn’t run as much as some of these other guys doesn’t make him any less dominant at his position.

2. O.J. Simpson

Buffalo Bills (1969-1977), San Francisco 49ers (1978-1979)

Not a lot of people want to sing the praises of O.J. Simpson today, and you won’t find oodles of his highlights on NFL media. I can’t imagine why. But putting the person aside, no one since the merger has been as dominant on the ground as Simpson, the best running back of the 1970s – and since the ‘70s were the worst modern decade for passing, the decade when running backs mattered the most, you could make a strong argument that Simpson was the most important running back since the merger, too.

Simpson was the only man to hit 2,000 rushing yards in a season before the NFL went to 16-game seasons. He still holds the 14-game rushing record and has never really been challenged; Jim Brown is in second-place at 1,863 yards, 140 behind Simpson. Even Adrian Peterson, in his 2012 run at the record, only had 1,812 in his first 14 games; that wouldn’t even match Simpson’s second-best 14-game total. When Lou Saban took over in Buffalo in 1971 and decided that hey, we should make this Simpson kid the focal point of our offense rather than having him block all the time, he simply became unstoppable, leading the league in rushing yards four times between 1972 and 1976. The 1973 MVP, with his juking, dodging elusiveness setting up his tremendous speed and acceleration was a household name in the ‘70s – the biggest individual attraction the league had and arguably the best open-field rusher of all time.

That won’t be what he’s remembered for.

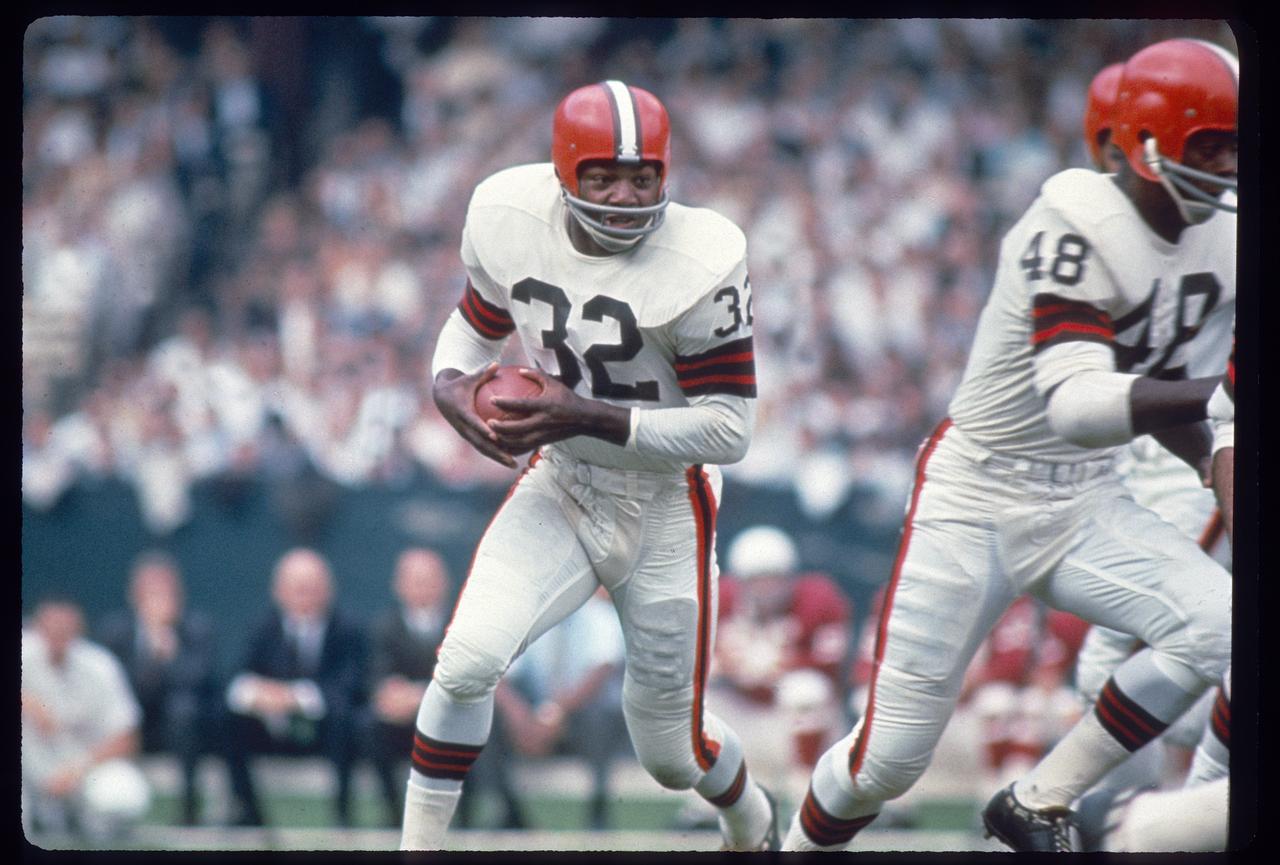

1. Jim Brown

Cleveland Browns (1957-1965)

Jim Brown played nine seasons in the NFL. He was the league’s leading rusher in eight of them. He led the league in yards from scrimmage and touchdowns five times each. He won the MVP in his first two seasons, fresh-faced and ready to dominate the league. He won the MVP in his final season, fed up and ready to move on to a movie career. In part because he never played through a decline period in his 30s, Brown is the only running back in NFL history to average more than 100 yards per game. He’s the only player to average over five yards per carry with at least 1,500 rushing attempts. The numbers speak for themselves.

And if the numbers didn’t speak for themselves, his contemporaries and followers would speak for them. There is no shortage of defenders from the ‘60s with stories about how terrifying it was to face Brown. Legends from Chuck Bednarik to Harry Carson to Paul Krause to Mel Renfro have long stories about trying to knock Brown out, only for him to get up without a scratch – or, worse yet, for him to run them over and drag them 15 yards down field. Paul Brown called him the greatest football player he ever saw. Running backs from every era – including names on this list like Emmitt Smith and Barry Sanders – have called Brown the greatest running back to ever play the game.

It’s possible Brown’s combination of power and agility has never been matched – not many 230-pound guys can run 4.5-40s, in pads, starting from a three-point stance. And the ones who can couldn’t knock people senseless like Brown could. “The key in the NFL,” Brown wrote in his autobiography, “is to hit a man so hard, so often, he doesn’t want to play anymore.” Add that to the mix with vision and perception 20 years ahead of its time, and that would be unfair in any era. In the 1950s, with the NFL still gradually taking its place as a predominant professional sports league? It was outright unfair. Jim Brown wasn’t a running back. Jim Brown was a force of nature; uncontained and uncontainable.

Brown’s legacy off the field is a complicated one. A long history as a respected and influential voice in the civil rights movement. An equally long history of allegations of assault, particularly against women, some of which resulted in jail time. You can view Brown’s life through any number of lenses, and come away with different opinions of his life’s work. On the field, however, there is no such grey area. A dominant peak? Brown’s entire career was his dominant peak. On the very, very short list of candidates for best football player of all time, Brown’s legacy on the football field has been set in stone for a very, very long time. Even half a century later, no one has been able to measure up to Brown’s best.